Daniel Merino, The Conversation and Nehal El-Hadi, The Conversation

If you want to know what happened in the earliest years of the universe, you are going to need a very big, very specialized telescope. Much to the joy of astronomers and space fans everywhere, the world has one – the James Webb Space Telescope.

In this episode of “The Conversation Weekly,” we talk to three experts about what astronomers have learned about the first galaxies in the universe and how just six months of data from James Webb is already changing astronomy.

The James Webb Space Telescope successfully launched into space on Dec. 25, 2021. After about six months of travel, setup and calibration, the telescope began collecting data and NASA published the first stunning images.

One of Webb’s nicknames is the “first light telescope.” This is because Webb was specifically designed to be able to see as far back as possible into the earliest days of the universe and detect some of the first visible light.

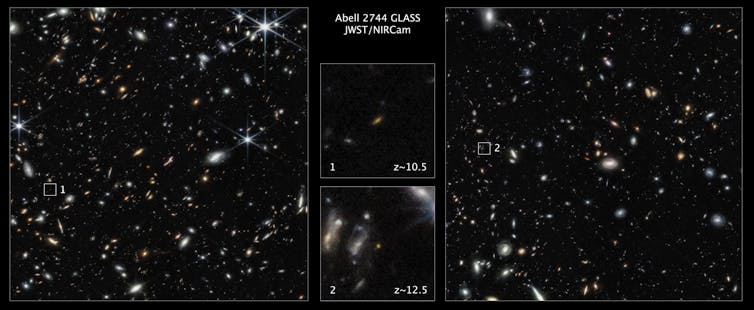

You can see these galaxies in the images NASA has released. Jonathan Trump, an astronomer at the University of Connecticut, is on one of the teams working on some of the early James Webb data. He was watching the release of the first images live and noticed some things many nonastronomers might have missed. “In the background, behind these beautiful arcs and spirals and massive elliptical galaxies are these tiny, itty-bitty red smudges. That’s what I was most interested in, because those are some of the first galaxies in the universe.”

NASA, ESA, CSA, Tommaso Treu (UCLA), CC BY-SA

To see any of these galaxies from the earliest days of the universe would be exciting, but right off the bat, Jeyhan Kartaltepe, an astronomer at the Rochester Institute of Technology, found something exciting when she started digging into the data.

“One of the things we’ve learned is that there are more of these galaxies than we expected to see.” In addition to working on identifying these early galaxies, Kartaltepe has been using Webb’s incredible resolution to study their structure and shape. “We expect there to be discs because discs form pretty naturally in the universe whenever you have something that’s rotating. But we’ve been seeing a lot of them, which has been a bit of a surprise.”

In addition to noting the shape of the galaxies in the early universe, astronomers like Trump are starting to be able to assess the chemical composition of these galaxies. He does this by looking at the spectrum of light James Webb is collecting. “We look at these distant galaxies and we look for particular patterns of emission lines. We often call them a chemical fingerprint because it really is like a particular fingerprint of particular elements in the gas in a galaxy.”

The universe started with just hydrogen and helium, but as stars formed and fused elements together, bigger, heavier elements started to emerge and fill in the periodic table as it is today. And just like Kartaltepe, Trump is finding evidence that things were happening faster in the early universe than astronomers expected. “I would’ve guessed that the universe would have struggled to make the periodic table and build up things. But that’s not what we found. Instead, the universe seems to have proceeded pretty rapidly.”

NASA/STScI

The discoveries coming out of James Webb are already changing how astronomers think of the early universe and challenging much of the existing theory. But the truly exciting part is that we are just beginning to see what this telescope is capable of, as Michael Brown, an astronomer at Monash University, explains.

“I’ve been on science papers that have used literally just a couple of minutes of data,” Brown says. “The image quality is just so good that a couple of minutes can do amazing things.” But soon Webb will begin to do follow-up surveys, take deep-field images and stare at parts of the sky for days and even weeks. Over the coming months, years and decades, Webb is going to keep giving astronomers plenty to work on, and astronomers like Brown are excited. “There is just all this complexity there, and we are barely scratching the surface. This will be the stuff that people who are students now are going to devote their careers to. And it’s going to be marvelous.”

This episode was produced by Katie Flood and Daniel Merino, with sound design by Eloise Stevens. It was written by Katie Flood and Daniel Merino. Mend Mariwany is the show’s executive producer. Our theme music is by Neeta Sarl.

You can find us on Twitter @TC_Audio, on Instagram at theconversationdotcom or via email. You can also sign up to The Conversation’s free daily email here. A transcript of this episode will be available soon.

Listen to “The Conversation Weekly” via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed, or find out how else to listen here.![]()

Daniel Merino, Associate Science Editor & Co-Host of The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation and Nehal El-Hadi, Science + Technology Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.